Research

Overall, I use digital evolution (evolving computer programs) to study evolutionary dynamics. I am broadly interested in the evolution of complexity, and my current projects focus on historical contingency in evolution.

I do not use digital evolution to replace traditional wet lab experiments, but to supplement them. My goal is synergistic collaboration, where digital evolution experiments are used 1) to run preliminary experiments that would be too risky to justify in a wet lab, 2) to perform work at scales not currently possible in wet lab experiments, and 3) to perform experimental controls that are infeasible in wet lab experiments. My favorite example, which is of the last variety, is Art Covert and collaborators’ work that reverted all deleterious mutations to empirically test if deleterious mutations were important to evolving populations.

Below, I have outlined some of my current projects and interests. The goal is to explain my thinking and help place my publications in context.

Historical contingency, potentiation, and replaying evolution

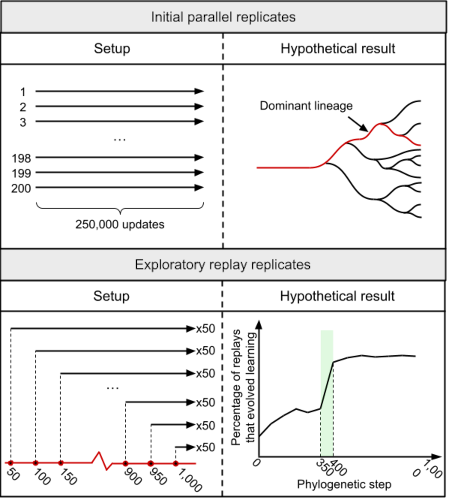

The concept of replay replicates, adapted from (Ferguson and Ofria, 2023).

Arrows in the left panes indicate evolutionary replicates.

The concept of replay replicates, adapted from (Ferguson and Ofria, 2023).

Arrows in the left panes indicate evolutionary replicates.

At any given point, we can summarize the potential future evolution of a population as a combination of adaptation, chance, and history (Travisano et al., 1995). With adaptation, we expect selection to favor more fit organisms. Chance comes into play via random mutations, genetic drift, etc. Here, we take history to mean everything before the current “starting point” of continued evolution.

I ask question about what happens as history changes (e.g., moving down a lineage). Examples include:

- When looking at a particular outcome, did the probability of that outcome change slowly over the course of the lineage, or were there steps that drastically altered that probability?

- At what point did the evolutionary outcome of the population become inevitable?

- How does the effect of history coincide with the traversal of the fitness landscape?

So far, my work has looked at the effect of history on the potentiation of a particular trait – the likelihood that particular trait eventually evolves. I quantify potentiation of this trait over time by performing analytic replay experiments. By seeding new evolutionary replicates along a lineage, we can see how many replicates at each time point evolved the behavior, showing us how potentiation of that trait varied over time. Both the concept of potentiation and the idea of analytic replay experiments come from (Blount et al., 2008), and I highly recommend the review of how reserachers have examined historical contingency in evolution (Blount et al., 2018).

So far, Charles and I have used analytic replays to investigate the evolution of associative learning in Avida (Ferguson and Ofria, 2023) (pdf). We found that potentiation can increase drastically, even with a single mutation. Now we’re working on expanding that study to look at trends across many more replicates, as well as simplifying things to examine potentiation in systems that are faster and easier to analyze.

The evolution of learning and phenotypic plasticity

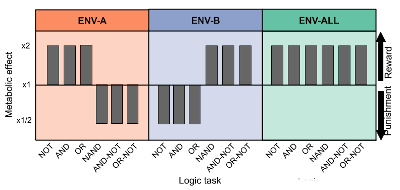

Conceptual figure from (Lalejini et al., 2021) showing the different environments.

Plastic organisms needed to switch their task phenotypes to handle ENV-A and ENV-B.

Conceptual figure from (Lalejini et al., 2021) showing the different environments.

Plastic organisms needed to switch their task phenotypes to handle ENV-A and ENV-B.

As mentioned above, I am broadly interested in the evolution of complexity. An interest in the evolution of learning was actually what brought me to grad school.

While my current work is investigating historical contingency, it is doing so in an associative learning domain. While I make no claims about how associative learning arose in natural organisms, this does allow us to ask questions about what conditions are suitable for associative learning to arise. This was inspired by work done by Pontes et al. on the evolution of associative learning in Avida (2020). In particular, my work has started to analyze the relationship between learning and pre-learning behaviors, such as correcting for errors.

I consider learning a subset of phenotypic plasticity, and I am interested in how plasticity arises and what effects it has on further evolution. Collaborators and I found evidence that, in a cyclical environment, plasticity stabilizes evolution such that the evolutionary dynamics closely resemble those in a static environment (Lalejini et al., 2021). I aim to continue this line of research after my PhD, further investigating how plasticity (and perhaps learning) can influence the evolution of additional complex behaviors.

Major evolutionary transitions

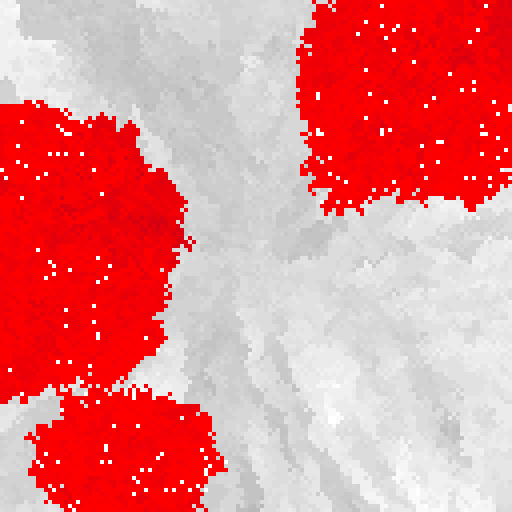

An example multi-cellular organism with cooperative (grayscale) and cheating (red) cells.

An example multi-cellular organism with cooperative (grayscale) and cheating (red) cells.

How did multi-cellular organisms arise from their single-celled predecessors? This is just one example of a major evolutionary transition. While the work I have done in major transitions has been limited, this is something I hope to return to soon.

Interested in how robustness and cooperation emerge in multi-cellular organisms, we found that spatial constraint alone can be sufficient for rudimentary robustness to evolve (Skocelas et al., 2022). Indeed, the larger the organism, the more higher the pressure for robustness (akin to Peto’s paradox).

Further inspiration for the value of digital evolution in studying major evolutionary transitions can be found in some of my favorite works, including the Dirty Work Hypothesis (Goldsby et al., 2014) and the new dishtiny system for studying fraternal transitions in individuality (Moreno and Ofria, 2019).

Software and standards

While my research interests are firmly rooted in evolutionary biology, the computer science side of me still enjoys writing software, especially versatile open-source software that promotes collaboration.

All of my current experiments are conducted in the Modular Agent Based Evolver 2 (MABE2). MABE2 allows users to construct digital evolution and evolutionary computation programs through a simple scripting language. Our goal is to make it incredibly simple to replicate and tweak almost any computational evolution experiment while being performant thanks to C++ under the hood. I am currently porting the digital evolution platform Avida to MABE2. If you’re evolving neural substrates (Markov brains, artificial neural networks, etc.), check out the original MABE!

MABE2 is built off of Empirical, a library for writing scientific software in C++. Empirical includes many basic components (pointer tracking, STL replacements with better debugging, etc.) as well as specifics such as evolutionary computation tools and support to compile for the web via Emscripten!

It is impractical, however, to expect all researchers to use the same code base for their experiments. As such, the first project I joined in grad school was on Data Standards for Artificial Life (paper) (GitHub). These proposed standards would ensure that, regardless of how it was gathered, data following the standard could leverage all standards-compliant tools.

Beyond these major projects, I’m always tinkering to improve my computational pipelines. This includes things like experiment pipelines and rolling queues on MSU’s high performaing computing cluster (which is wonderful!), to simple Python packages I’ve pieced released from time to time (pyvarco), and to a framework to test your Avida implementation.

Beyond the software I’ve written / helped write. My current obsession is network-based notetaking in Obsidian.

Miscellaneous evolution projects

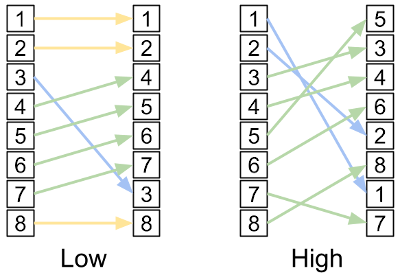

Example of low and high epistasis, as determined by the change in mutant rankings.

Example of low and high epistasis, as determined by the change in mutant rankings.

Rank epistatis started as a class project but is now something I’d like to get back to. Instead of relying on fitness baselines, which can be tricky to calculate in natural organisms, we used the relative ordering of mutants to measure the epistasis of genetic sites (Ackles et al., 2020). If the ranking of mutants drastically changes when a site is changed, we can infer that epistasis must be at play.

Most of my current work uses digital evolution to refine our understanding of evolution itself. However, previous work has looked into the selection schemes used in evolutionary computation. Specifically, we analyzed the effects of applying subsampling to lexicase selection.